United States-Canada Tax Treaty

Canada’s International Tax Compliance Rules

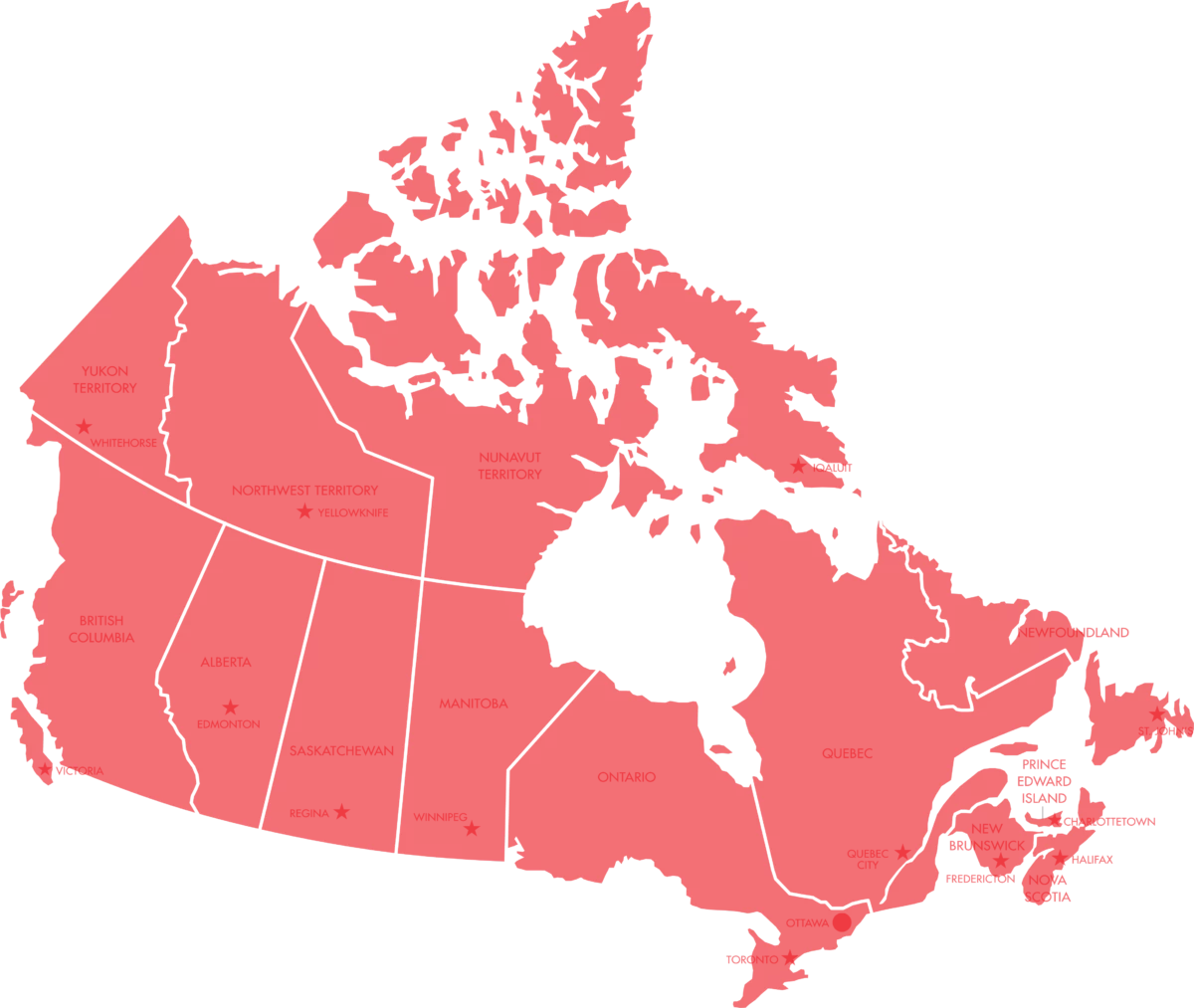

US – Canada Tax Treaty Quick Summary. In 1867, the United Kingdom passed a Parliamentary act establishing what is now known as Canada. Today, Canada, the largest country in the Western Hemisphere, is a federation of ten provinces and three territories.

Following its formation in 1867, Canada’s new government was provided with the power to raise money by taxation. Moreover, the new government was divided between the federal government and the provincial governments. Generally, the federal government was tasked with providing railways, roads, bridges, and harbors. Conversely, the provincial governments were responsible for providing its citizens with education, health, and welfare.

Canada’s federal government did not initiate a formal income tax until World War I. Due to its involvement in the war and its need for war funds, Canada’s federal government established a corporate tax in 1916. A year later, the federal government introduced the Income War Tax Act, which added an income tax regime on individuals. In 1948, the Income War Tax Act was replaced with the Income Tax Act. Today, the Canada Revenue Agency and various provincial governments administer the federal and other tax laws in Canada.

Under Canada’s system of government, tax laws arise through the enactment of Parliamentary and provincial acts and legislation, tax treaties, regulations, and case law. Its primary tax laws derive from the Income Tax Act (RSC 1985, c. 1, 5th Supp.), Excise Tax Act (RSC 1985, c. E-15) and other federal and provincial legislation.

Recent tax measures include 100% first-year deduction (capital cost allowance) for certain manufacturing and processing equipment, changes in the treatment of derivative forward agreements, foreign affiliate dumping rules, transfer-pricing rules, and rules with respect to cross-border securities lending arrangements, employee stock options, and mutual fund trust redemptions.

Effective July 1, 2020, Canada is a member of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (CUSMA)

U.S-Canada Tax Treaty

Canada Tax Treaty

- Convention between the United States of America and Canada with respect to Taxes on Income and Capital, Washington on September 26, 1980

- Technical Explanation of the Convention between the United States and Canada signed on September 26, 1980

- PROTOCOL AMENDING THE CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND CANADA WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME AND ON CAPITAL

- Technical Explanation of the Protocol signed at Chelsea on September 21, 2007 (the “Protocol”), amending the Convention between the United States of America and Canada with Respect to Taxes on Income and on Capital

Currency. The official currency of Canada is the Canadian dollar (CAD). It is a free-floating currency.

Common Legal Entities. Canadian law permits various forms of business organization. These include sole proprietorships, partnerships, joint ventures, limited partnerships, corporations, unlimited liability companies, and trusts.

Careful attention is required when formally organizing a business in Canada, particularly in light of requirements that may apply at the federal and provincial levels. For example, the federal government and various provincial governments have enacted separate legislation providing for the formation and regulation of corporations.

On April 29, 1999, the Canadian Parliament passed the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency Act, establishing the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (now referred to as the Canada Revenue Agency). The Canada Revenue Agency is responsible for the administration of various tax programs in addition to the delivery of economic and social benefits to citizens of Canada. It also helps administer certain provincial and territorial tax programs. In addition, certain provinces have separate taxing authorities to administer their provincial tax systems.

Tax Treaties.

- Canada is a signatory to 93 income tax treaties, as well as the OECD MLI.

- United States-Canada Tax Treaty. The United States and the Canadian federal government have entered into a tax treaty and five amendments, known as “Protocols” (collectively, the “US-C Treaty”). The last Protocol entered into force on December 15, 2008, and generally took effect on January 1, 2009. Significantly, under Canada’s system of laws, the federal government is unable to enter into international agreements for or on behalf of the provincial governments. Accordingly, provinces may levy taxes on their own, regardless of provisions in the US-C Treaty. Thus, careful attention may be required in analyzing any treaty benefits under the US-C Treaty. Some of the US-C Treaty benefits are discussed below.

- Dividends. Generally, under the US-C Treaty, dividends are subject to a reduced withholding tax rate of 15-percent. However, the withholding rate may be reduced to 5-percent if the beneficial owner is a company that owns 10-percent or more of the voting stock of the company making the dividend payment. Interest. Under the Fifth Protocol, interest payments between residents of Canada and the United States are generally not subject to withholding tax. Royalties. If royalties arise in one country and are paid to a resident of the other country, the royalty payments are generally subject to a reduced withholding tax rate of 10-percent. However, certain types of royalties are excluded from the reduced withholding tax rate. Business Profits. Generally, business profits of a resident of a contracting state are not taxable in the other contracting state unless the resident conducts business in the latter state through a permanent establishment. If this applies, the resident may be taxed in the latter state to the extent any business profits are attributable to the permanent establishment. Personal Services. Independent personal services income derived by an individual resident of a contracting state may be taxed in the other contracting state to the extent such individual has a permanent establishment regularly available in the latter contracting state and the independent personal services income is attributable to the permanent establishment. For employment income, a resident of a contracting state may be taxed in the other contracting state to the extent employment is conducted in the other state, subject to some exceptions.Gains from Real Property. If a resident of one contracting state has gains from the sale or disposition of real property located in the other contracting state, it may be taxed by the latter contracting state.

Corporate Income Tax Rate. Generally, the Canadian federal corporate net tax rate is 15%. However, the rate may be reduced for certain Canadian-controlled private corporations claiming a small business deduction. In these instances, the federal corporate net tax rate is 9%, effective January 1, 2019.

Provinces and territories also impose additional corporate taxes on corporations. Currently, these may range from as low as 0% (Manitoba) to as high as 16% (Prince Edward Island).

Individual Tax Rate. Similar to the United States, Canada’s federal government imposes graduated tax rates on the taxable income of individuals. For 2020, these graduated rates range from 15% to 33%.

Provinces and territories also impose separate graduated tax rates on individuals. Currently, these may range from as low as 4% (Nunavut) to as high as 21% (Nova Scotia).

Capital Gains Tax Rate. Canada provides a 50% exclusion from capital gain. In addition, taxpayers may claim allowable capital losses. However, capital gains are subject to ordinary income tax rates. In certain cases, Canadian tax law permits an exemption from the recognition of capital gain, e.g., the sale or disposition of an individual’s principal residence.

Residence. Unlike the United States, Canada does not tax on the basis of citizenship. Rather, an individual is subject to Canadian taxation based on such individual’s residency. In making this determination, Canada looks to whether the individual has a home or personal property in Canada, a spouse or common-law partner and dependents in Canada, and any other social or economic ties to Canada. Regardless, an individual without residential ties to Canada will be treated as a resident if he or she is present in Canada for 183 days or more in a given tax year. If an individual is a resident of Canada, he or she is subject to tax on worldwide income from all sources.

Similarly, Canadian-resident companies are subject to tax on their worldwide income. Generally, a company is considered a resident of Canada if it is incorporated in Canada or if its management and control is located in Canada.

Withholding Tax. Canada imposes a 25-percent withholding tax on dividends, interest, and royalties paid to nonresidents. In addition, Canada imposes a 15% withholding tax on services rendered in Canada by nonresidents. Canada also has other withholding taxes, such as withholding taxes for payments made out of certain retirement plans.

Branch Profits Tax. Canada imposes a 25-percent branch profits tax.

Canada employs an arm’s-length standard, with a “reasonable efforts exception.” Canada has adopted country-by-country reporting (CbCR) for certain multinational enterprises (MNE) groups, generally following BEPS action 13.

CFC Rules. Canadian residents are subject to a current tax on an allocable share of foreign accrual property income (FAPI) earned by a controlled foreign affiliate. Anti-avoidance rules may apply.

Thin Capitalization. Canada provides thin capitalization limitations on interest deductions to specified non-resident persons.

Inheritance/Estate Tax. Canada does not generally have an inheritance or estate tax. However, certain gifts may be treated as deemed sales. In addition, a deceased taxpayer is deemed to have disposed of the property prior to death at fair market value.

Overview of Canada’s Income Tax System. Canada imposes a federal income tax on the income of individuals and companies, based on residency. In addition, provincial taxes are imposed on the income from activity within the provinces. Non-residents are generally subject to tax on income from Canadian sources and on gains from the disposal of taxable Canadian property. The Canadian corporate tax system attempts to alleviate the double taxation of income through the implementation of a modified imputation system, which provides a tax credit with respect to dividends paid by domestic corporations to individuals.

Individuals. Canadian resident individuals are subject to income tax on their worldwide income. Each individual must separately compute his or her tax liability, and family members may not file joint income tax returns. Gross income is divided among several categories, including employment income, business income, property income, and capital gains.

Property income consists of passive income earned through investment activities. In computing gross income, resident taxpayers determine their income and losses for each category separately. All sources of income are then aggregated before the taxpayer calculates taxable income. Individuals are also subject to an alternative minimum income tax.

Individual taxpayers are entitled to deductions for a limited number of personal expenses, including childcare expenses incurred to allow the individual to work or obtain education. Individuals may also claim a number of credits, which are calculated by multiplying an allowance by the lowest tax rate.

Dividends, interest, and royalties are subject to tax, and the expenses incurred to produce investment income generally are deductible. Dividends paid by domestic companies are taxable at a reduced rate. An individual’s effective tax rate on dividends depends on the province and generally is equal to that on capital gains. The rate reduction is accomplished by means of an imputation tax credit under which a shareholder is permitted a credit on the grossed-up dividend.

The gross-up amount equals one-fourth of the dividend and theoretically represents the corporate income subject to corporate-level tax. The dividend credit amount, which is based on the gross amount of the dividend, represents the corporate tax paid on the distributed dividend. One-half of capital gains are included in income, and a Canadian resident is entitled to an exemption over his lifetime on gain from the disposition of either a qualifying farm or shares of a Canadian-controlled private corporation that uses substantially all its assets in carrying on an active business primarily in Canada.

Corporations. Canadian resident corporations are taxable on their worldwide income from business income, property income, and capital gains. Property income consists of passive income earned through investment activities. Business income is taxable at full rates, property income is generally taxable at full rates with certain exceptions for dividends, and 50 percent of capital gain is included in income.

Expenses are generally deductible to the extent they are reasonable and incurred for the purpose of gaining or producing income and, if related to capital structure (i.e., an amount deducted with respect to an outlay, loss, or replacement of capital), to the extent the deduction is expressly permitted by the Income Tax Act. Expenses are not deductible if they are incurred for the purpose of gaining or producing exempt income or if they are incurred solely for the purpose of realizing capital gains. In general, financing expenses, royalties, and inter-corporate dividends are deductible. Interest expense that is on capital account is deductible only in accordance with statutory rules.

Canada levies taxes at both the individual and the shareholder level, although the double taxation is partially eliminated through a modified imputation system. A notional dividend tax credit provides tax relief with respect to domestic dividends paid to individuals. This credit does not fully compensate for corporate tax paid in the case of active business income of a Canadian-controlled private corporation in excess of an annual limit, income earned by a publicly traded domestic corporation, income earned by a nonresident controlled corporation, or income earned by a publicly traded domestic corporation.

Corporate entities resident in Canada are generally subject to tax on their worldwide income at rates that depend on the status of the corporation and the type and location of income earned. A corporation is considered to be a Canadian resident if it was incorporated in Canada or, if incorporated outside of Canada, its central management and control is located in Canada.

Corporate groups are not permitted to file consolidated tax returns, but special rules govern the treatment of intra-group income. Dividends are includible in income, and a corporation generally may claim an offsetting deduction to the extent it receives dividends from a taxable resident corporation. The deduction is not available for preferred shares more similar to debt than equity. A tax may be imposed on dividends on preferred shares if the corporation paying the dividend has not paid a minimum level of tax on the income generating the dividend.

Partnerships. Similar to United States tax law, Canadian tax law does not recognize a partnership as a separate taxpayer. Accordingly, each partner of a Canadian partnership is subject to tax on such partner’s share of partnership income each year, regardless of whether distributions are made from the partnership to the partner.

Because the Income Tax Act does not contain a definition of a partnership, Canadian courts and the Canada Revenue Agency look to the rights and obligations between the parties in accordance with the governing provincial jurisdiction.

Other Taxes. Each province imposes a provincial corporate income tax. Canadian municipalities may impose business license fees but do not impose income taxes. The province imposes royalties or taxes on income from oil, gas, and mining operations. The federal government imposes capital taxes on financial institutions and on life insurance corporations. The capital taxes effectively are a form of minimum tax, and income taxes and corporate surtaxes may be credited against them. Corporations generally may carry over unused credits from other years to reduce capital taxes due.

Canadian provinces also impose real estate taxes, typically at the municipal government level, and capital taxes on corporations with a permanent establishment in the province.

Inheritance and Gift Taxes. Though Canada imposes no inheritance or gift tax on its residents, deemed disposition provisions effectively impose a taxation on such transfers. Specifically, if a person gifts property to another individual, Canada’s tax system deems the donor to have received proceeds equal to the fair market value of the gifted property. This may cause the donor to recognize income, recaptured depreciation, or capital gains. Similar rules apply to dispositions on death. Significantly, however, spouses may transfer property to each other either by gift or on death without triggering a deemed receipt of proceeds.

Payroll Taxes. Several Canadian provinces impose payroll taxes, which are used to finance social insurance programs. Employees must contribute, up to maximum annual limits, to a federal unemployment insurance fund and pension plan that provides retirement, disability, and certain other benefits. Every month, employers are responsible for collecting and remitting the employees’ portions, as well as their own portions.

The provinces each administer their own general health insurance and accident plans to assist residents with the cost of health care and to compensate employees who have been injured at work.

Indirect Taxes. Canada imposes a form of a value added tax known as the goods and services tax (GST). The tax generally applies to all domestic transactions, including certain transfers of real estate. The tax also applies to imported goods; imported services are subject to the tax if the service recipient is not registered for GST purposes. The GST is charged at each stage of the economic chain, and venders are able to claim refunds in the form of input tax credits of tax paid.

Because the final consumer is not able to claim an input tax credit for GST paid, the tax is ultimately borne by the final customer. The standard rate is six percent. Certain goods and services, such as food, medical devices, some agriculture and fishing products, residential rents, most health and dental services, certain educational services, domestic financial services, and the sale of previously owned residential housing, are exempt. Goods and services exported outside Canada are also exempt.