Background

The House Committee of Ways and Means (the “House”) has been busy the last few days. Indeed, the House continues to mark up and work through potential revenue raisers (i.e., tax increases) to help pay for recent legislative proposals. Although these proposals are not yet law, tax professionals should keep a careful eye on the proposals to ensure that they do not potentially interfere with their client’s tax planning. At a very minimum, tax professionals should be knowledgeable enough to discuss the proposals with their clients and how such proposals (if eventually enacted into law) would impact their clients’ overall goals and objectives.

Income Tax Rates

Increasing income tax rates is generally the easiest way to raise additional revenue for the government. And, the proposals are no different in proposing additional income tax increases. These potential increases are discussed below.

Individual Income Tax Rates

Individual income tax rates are currently housed in section 1 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”). The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, Pub. L. No. 115-97 (the “TCJA”) reduced income tax rates for individuals. Under the TCJA, the top income tax rates for tax years 2018 through 2025 were reduced from 39.6 percent to 37 percent. However, the reduced rates were not permanent and were set to sunset in 2026, i.e., the top rates were set to revert back to 39.6%.

The House proposal seeks to increase these reduced rates from 37 percent to 39.6 percent for the 2022 and later tax years. In addition, the proposal seeks to bring more high-income earners into the higher marginal tax rate of 39.6 percent through a reduction of income subject to the higher rate. For example, under existing law, taxable income of over $538,475 for a single individual is taxed at 37 percent. Under the proposal, taxable income over $501,250 would be taxed at 39.6 percent for a single individual.

Corporate Income Tax Rates

Because I am an adjunct corporate income tax professor, corporate income tax rates always interest me. Currently, those rates are fixed at 21 percent. See I.R.C. § 11. But, that was not always the case—indeed, corporate tax rates were graduated in prior years with much higher tax rates.

The House proposal seeks to increase the top corporate income tax rate from 21 percent to 26.5 percent. This 26.5 percent rate would apply to corporations with taxable income in excess of $5 million.

Significantly, however, corporations with $400,000 or less of taxable income would enjoy a reduced corporate income tax rate—that new rate would be reduced from 21 percent to 18 percent. And, the proposal would effectively leave the marginal corporate income tax rate the same for corporations with income over $400,000 but less than $5 million, i.e., such income would be taxed at 21 percent.

Capital Gains

Generally, taxpayers enjoy a tax preference when they hold capital assets that appreciate in value. Although the capital asset may appreciate each year, the taxpayer is not required to report the gain until there is a disposition of the asset, i.e., the disposition has been “recognized” for federal income tax purposes. See I.R.C. § 1001.

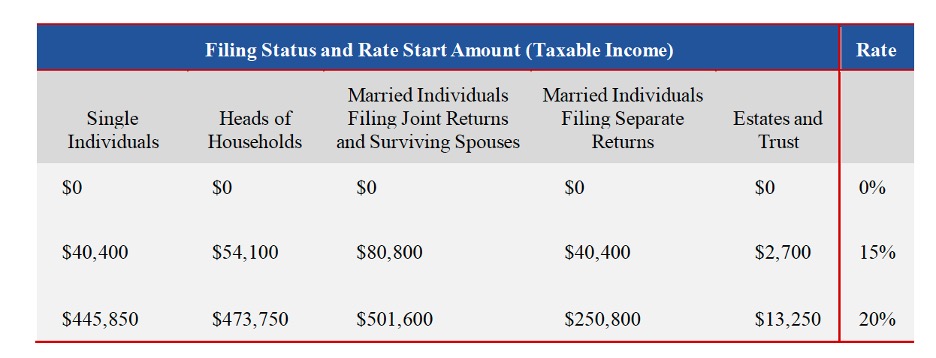

Capital gain tax rates are also subject to preferential income tax rates (and, they have been for some time). Generally, these rates are lower than the ordinary income tax rates, provided the taxpayer has held the capital asset for more than one year. See I.R.C. § 1222. For tax year 2021, the long-term capital gain tax rates are as follows (based on filing status and taxable income):

Generally, capital gains are also subject to net investment income tax (“NIIT”), which adds an additional 3.8% tax, but only if the individual meets certain income requirements. Accordingly, maximum long-term capital gain rates can be as high as 23.8 percentfor high-income earners.

Under the House proposal, Congress would increase the top regular capital gain rate from 20 percent (without NIIT) to 25 percent. Thus, total long-term capital gain rates could be taxed as high as 28.8 percent.

Termination of Temporary Increase in Unified Credit

Federal tax law imposes both an estate tax and a gift tax. The two taxes effectively work together. Accordingly, the gift tax is imposed on certain lifetime transfers, whereas the estate tax is imposed on certain transfers at death. Either way, the IRS collects taxes.

Because these two taxes work together, current federal tax law provides a unified credit for transfers by gift and at death. See I.R.C. § 2010. For decedents dying and gifts made after January 1, 2018, the basic exclusion amount that is used to determine the unified credit is $5 million, indexed for inflation for decedents dying and for gifts made after 2011. And, the basic exclusion amount further increases (at least temporarily) for estates of decedents dying and gifts made after December 31, 2017, and before January 1, 2026. Under this temporary increase, the basic exclusion provided in section 2010(c)(3) doubles from $5 million to $10 million (indexed for inflation). For 2021, the basic exclusion amount is $11.7 million, indexed for inflation.

The proposal seeks to do away with the temporary increase of the basic exclusion. Specifically, under the proposal, if a decedent dies or a person makes a gift after December 31, 2021, the basic exclusion amount applicable would be $5 million, adjusted for inflation. Based on today’s inflation numbers, that amount would be approximately $6,020,000 for 2022.

Repeal of Section 6751(b)

I have written extensively on section 6751(b), and its requirement that IRS managers review penalty determinations prior to lower-level IRS employees formally communicating the penalty determination to the taxpayer. For example, see here, and here.

Incredibly, the proposal seeks to overturn all of the taxpayer-friendly decisions regarding section 6751(b) managerial approval. Indeed, instead of a full abatement of the penalty, the proposal would merely require that “appropriate IRS supervisors certify quarterly to the Commissioner that they are in compliance with the statutory requirements of section 6751(a) [sic] and related policies of the IRS.” Stated differently, taxpayers will have no recourse if a manager fails to certify the penalty as appropriate under the circumstances.

Qualified Small Business Stock

Section 1202 of the Code provides fairly taxpayer-friendly rules regarding the sale of so-called “qualified small business stock.” If used properly, a taxpayer may be able to exclude all of his or her capital gain on the sale of the stock up to the greater of: (1) ten times the taxpayer’s adjusted basis, or (2) $10 million.

The proposal would reduce the capital gain exclusion from 100 percent to 50 percent for shareholder-taxpayers who have $400,000 or more of adjusted gross income.

FDII and GILTI Changes

Domestic corporations generally enjoy preferential tax rates on their foreign-derived intangible income (“FDII”) and their global intangible low-taxed income (“GILTI”). This preferential treatment derives from section 250 of the Code.

More specifically, section 250 permits a current deduction of 37.5 percent of a domestic corporation’s FDII. See I.R.C. § 250(a)(1)(A). However, for tax years after 2025, the FDII deduction under section 250 will be reduced to 21.875 percent. Because the deduction amount is reduced in 2026, the effective United States income tax rate will increase.

The preferential tax rate on GILTI works similarly. Currently, corporations are permitted a deduction equal to 50 percent of their GILTI. See I.R.C. § 250(a)(1)(B). But, for tax years after 2025, the deduction for GILTI is reduced to 37.5 percent.

To raise additional revenue, the proposal seeks to reduce the FDII and GILTI percentages. Specifically, for tax years after 2021, the FDII percentage would be 21.875 percent, and the GILTI percentage would be 50 percent.

Conclusion

Taxpayers and their tax professionals should carefully watch the House’s proposals to determine whether any proposals become law. This particularly applies to domestic corporations with foreign operations and wealthy, high-income earning taxpayers.

Freeman Law aggressively represents clients in tax litigation at both the state and federal levels. When the stakes are high, clients rely on our experience, knowledge, and talent to help them navigate all levels of the tax dispute lifecycle—from audits and examinations to the courtroom and all levels of appeals. Schedule a consultation or call (214) 984-3000 to discuss your tax needs.