Introduction

In this revenue ruling, the Service addressed the application of the economic substance doctrine to certain basis-shifting transactions which result from the operative rules of Subchapter K. Generally, the Service identified the issue as taxpayers using the rules applicable to partnerships to create disparity between inside and outside bases.

As a result, the partnership and partners use §§ 732, 734(b), and 743(b) to shift basis. In the most extreme hypothetical sense, this may result in basis retained in non-depreciable property being shifted to property that qualifies for treatment under § 168(k).[1] These transactions may also simply produce less gain upon final disposition of the property due to the increased basis.

Rev. Rul. 2024-14 Situation 1

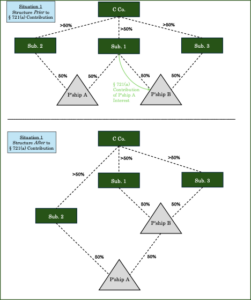

This article reviews Situation 1 and includes a visual depiction of the pre- and post-transaction structure at the end. The illustration is likely more illuminating, but I’ll concisely state it here.

C is a domestic corporation owning greater than 50% of Sub 1, 2, and 3. Sub 1 and Sub 2 are equal 50% partners in Partnership A. Similarly, Sub 1 and Sub 3 are equal 50% partners in Partnership B. As the Service prescribed in the ruling, the business purpose of the transaction was to effectuate cost savings.[2] In Situation 1, Sub 1 contributes its interest in Partnership A to Partnership B.

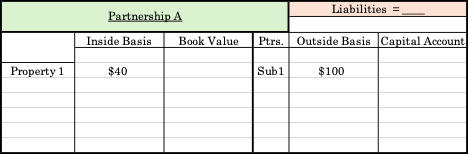

According to the ruling, the partnership had an adjusted tax basis (inside basis) in partnership property of $40[3]. As Sub 1 was a 50% equal partner, Sub 1’s share of that inside basis was $20. At that time, Sub 1 had an outside basis of $100. Of important note, the Service provided that the partners specifically intended to create the disparity between outside and inside basis.

A simple partnership balance sheet follows:

Therefore, following the § 721(a) tax-free contribution, the transferee-partner—Partnership B—would take a transferred basis, increased by any gain recognized.[4] Accordingly, Partnership B’s outside basis equals $100. If the partnership did not have a valid § 754 election in place, the inside basis of the partnership property would remain at $40 and no special basis adjustments would be made to partnership property or the outside basis of the new transferee-partner.[5] However, the ruling provides that the partnership made a valid § 754 election. Thus, the operative rule mandates basis adjustments under §§ 734 and 743.

Under § 743(b), the transferee-partner shall receive a special inside basis adjustment. In the normal course, the transferee-partner would be purchasing the partnership interest just like purchasing stock, but because the partnership acts like a conduit the partner is entitled to basis credit in the assets of the partnership.[6]

As a result, the mechanical rules provide for a special basis adjustment of $80—which is the difference between the transferee-partners outside basis ($100) and that partner’s share of the adjusted tax basis of partnership property ($20). Pursuant to Subchapter K basis allocation rules and this ruling, the special inside basis adjustment is allocated towards depreciable property. § 755; Treas. Reg. § 1.755-1(b)(5).

Notably, again, the Service states that the partners were acting with the specific intent to achieve this result. Furthermore, the Service states that the business purpose—general cost savings—was “insubstantial” in comparison to the reduced aggregate Federal income tax liability. Presumably, this means the transaction produced tax cost savings in excess of the operational cost savings.[7]

Rev. Rul. 2024-14 Holding

In doing so, the Service concludes that the transaction lacked economic substance under § 7701(o). The revenue ruling does an exceptional job at laying out the economic substance doctrine codified under § 7701(o). Briefly, a transaction and its corresponding tax benefits must possess economic substance and a business purpose.[8]

Accordingly, as the Service contends that the transaction lacks economic substance[9], the transaction is recast under the “Holding(s)” subheading. As such, under Rev. Rul. 2024-14, the basis adjustment under § 743(b) shall be disregarded. Therefore, Partnership B shall never receive a special inside basis step-up in its share of partnership property. Thus, the inside basis with respect to the transferee-partner remains $20.

Loper Considerations

In using traditional methods of legal analysis, the Service provides insight on the case law that it might use in a future dispute. Furthermore, the author of the ruling substantiates the position taken with a review of the congressional record and congressional intent.

Critically, this would be important in future litigation under the new Loper standard as opposed to Chevron.[10] While the ruling is sensible, it may be that a more reasonable or equally reasonable legal position is available. Thus, without mandatory application of reasonable agency interpretation, a reviewing court would have actual discretion.

Structure Depiction

_______________________________

[1] § 168(k), as modified by the 2017 Tax Act, provided for accelerated cost recovery on depreciable property. The amount of the acceleration was graduated through intermittent sunset provisions. § 168(k)(6). However, its first iteration allowed for taxpayers to fully deduct the cost of depreciable property in the current taxable year. § 168(k)(6)(A)(i). The current rate is 80%. § 168(k)(6)(A)(ii).

[2] Interestingly, the revenue ruling never mentions whether this analysis is made on present value terms. The reduction in administrative costs would exist for many years to come and thereby produce a present value greater than the current year’s costs saving. Thus, as the ruling discusses substantiality, it would be consistent to undergo a DCF to ascertain the true value of cost savings apart from the Federal tax cost savings. Under the “Law” subheading, however, the ruling does mention when present value terms are considered under the economic substance doctrine. § 7701(o).

[3] I have assumed this figure based on the facts as stated. However, the revenue ruling vaguely asserts that the partners created the disparity through certain contributions and distributions to each partner and noting that these transfers were made in accordance with § 704(b)-(c).

[4] § 723.

[5] There is an exception to this general rule. See, §§ 734(a), (d) (relating to substantial basis reduction) and 743(a), (d) (relating to substantial built-in loss).

[6] In most cases, the transferee-partner is entitled to the basis adjustment because the partnership has made a valid § 754 election.

[7] And, as mentioned above, this analysis does not appear to take into account any future cost savings in present value terms. Moreover, the ruling doesn’t analyze whether C would be able to use the deductions in the current taxable year. Although, given the language of the ruling, it may be safe to assume the tax cost savings are being used in the current year.

[8] § 7701(o)(5)(A).

[9] Rightfully so, as one of the assumptions in the ruling was the specific intent to avoid Federal income taxes.

[10] Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, 144 S. Ct. 2244 (2024); Chevron v. Natural Res. Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984).